If one is interested in dance history, then the mention of Geneva is likely to trigger two associations: Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) and Emile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865-1950); both are known (amongst other things) as educational theorists, composers and musicians. It is natural to ask whether any connection existed between Revuz and these much more famous figures. Indeed, Revuz was well aware of both and he organised performances of the music and dance of Rousseau and Dalcroze. Both were famous in Revuz’s lifetime as citizens of Geneva and their worlds overlapped in space and time respectively; the house where Rousseau was born was in the street where Revuz had his first school, whilst Dalcroze and Revuz were contemporaries in Geneva. However, Revuz and Dalcroze did not coexist professionally in Geneva for long; by 1910, Dalcroze had been invited to found a new school in Hellerau, near Dresden. There is no evidence to show whether Revuz ever met Dalcroze, though it seems very likely that he would have seen Dalcroze perform. In August 1907, the Musical Times reports that in Geneva “M. Jaques-Dalcroze gave a course of six lectures, with practical illustrations, on ‘Rhythmical gymnastics.’ ” If Revuz attended these, he does not mention this in the notebook.

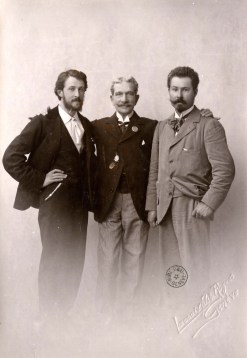

Benjamin Archinard

The first, indirect connection between Revuz and Dalcroze comes through the dance teacher Archinard, whom Revuz succeeded in 1904; Revuz’s early advertisements in the Journal de Genève make a point of the fact that he was the successor to this renowned teacher. Archinard had a long-standing association (since 1851 at least) with the Fêtes des Vignerons (the Winegrowers’ Festival). This festival included a costume parade with stops along the route for set-piece dances, which Archinard arranged, and large-scale choral works (several hundred members of choral and gymnastic societies took part in these performances). Following these very successful parades, Archinard collaborated with Dalcroze and the poet Daniel Baud-Bovy on a spectacle for the Exposition nationale de Genève in 1896, entitled Poème alpestre [1]; the music was composed by Dalcroze and dedicated to Vincent d’Indy. The dedication, from liberal, Calvinist Geneva to a Catholic anti-Dreyfusard, and that during the period of the affaire Dreyfus, seems somewhat remarkable.

Left to right: Baud-Bovy, Archinard, Dalcroze. Picture: Bibliothèque de Genève

Although Archinard clearly could rise to the occasion to choreograph large-scale new works, his dance school focused on teaching the popular salon dances of the day to the public; Revuz apparently continued Archinard’s day-to-day business in a similar style.

Emile Jaques-Dalcroze

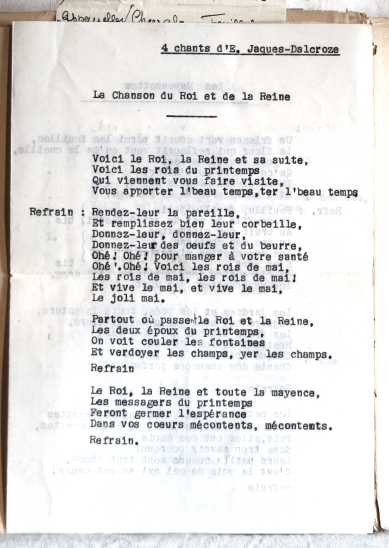

Another connection is made by the loose pages tucked into the notebook containing the text of four of Dalcroze’s songs “Chants d’Été” (La Chanson du Roi et de la Reine, Les Mayenzettes, Les quatr’fous, Prière patriotique) . It is not evident what the occasion was at which these songs were performed, but it is most likely the folkloric Soirée de Ceux de Genève held in 1957, at which several choral pieces and songs by Dalcroze were performed, whilst Revuz directed the (by now) nostalgic “dances of our grandmothers”, as they were described in a review in the Journal de Genève. Perhaps someone who reads this took part in that event and can clarify this?

In 1965, the year before Revuz died, the choir of Ceux de Genève and other artists produced a commercial LP (apparently their their only venture of this kind) commemorating the centenary of Dalcroze’s birth and entitled Le Jeu Du Feuillu. (Philips P625 102L). Dalcroze’s music is no longer widely performed and is generally considered rather unoriginal but, in Geneva, he was a local hero and his music had regional, nationalistic appeal.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The connection to Rousseau comes likewise through dance: on the 18th August, 1934, Ceux de Genève performed the dance Allons danser sous les ormeaux from Rousseau’s opera Le devin du village in the municipality of Presinge in Geneva, for local film-makers; Revuz was responsible for the choreography. The theme of dancing under the elms (sous les ormeaux; e.g, Watteau’s ‘The Shepherds’) is an archetype of traditional French music. Rousseau absorbed the image as a child from the singing of his step-mother; in Confessions he recalls the powerful effect on him of an early eighteenth century brunette she sang about Tircis playing his chalumeau under the elms [2]. Rousseau used this archetype for the ‘big dance number’ of Le devin du village though, surprisingly, the dance is set to a jig rhythm (suggested strongly by the rhythm of the title) that seems to have more connection to Italian than French folk dance.

- P. Budry, La Suisse qui chante (Freudweiler-Spiro, Lausanne 1932)

- D. Fabre, L’Homme, Connaît-on la chanson? (2015), 15-46